Year of the Falco

![]()

Year of the Falco |

|

Reborn as a homebuilt, the Sequoia Falco F.8L has finally

emerged.

And what a beauty it is.

by Nigel Moll

This article appeared in the February 1986 issue of Flying. |

Atop a hill in Roseville, California, stands one of the world's smallest aircraft factories. You could drive past without noticing, because there's no sign announcing Hansen Aircraft Corporation or Hansen Industries or anything quite so grand. The place is camouflaged to look like one more home in a quiet residential neighborhood, and just one airplane has rolled through the doors in two years.

The airplane is a Ferrari-red, aerobatic Sequoia Falco, a breed of homebuilt that had become something of a riddle among those who build their own airplanes. It was the slender, complex Italian you built from a kit, the pet project of a Virginian perfectionist who had bitten off more than he could chew. In a nutshell, they said it would never fly.

Eat 'em up, naysayers. For two years, Karl Hansen's airplane has been as demanding of time and attention as a new child, but now, along with a growing number of Falcos (10 at last count), it has flown the nest. And as a breed, the Falco has joined ranks with the Christen Eagle as one of the classiest acts in homebuilding. It was Frank Christensen's Eagle kit that Alfred Scott, the Virginian behind the renaissance, tried to match in terms of completeness and intelligibility, and by all accounts he has succeeded admirably.

Hansen's is not the first homebuilt Falco: that honor is shared by Larry Wohlers, who built the first Falco from Sequoia plans (not a kit) and flew it in 1982; and Dave Aronson, who completed the first kit-built Falco in time to fly it to the 1984 EAA convention at Oshkosh. While flying to the 1985 Sun 'n' Fun Fly-in at Lakeland, Florida, however, Aronson's Falco reportedly ran out of gas during a night instrument approach, and he died in the crash.

To start the story at the beginning, it's necessary to go back 30 years. Tri-Pacers were high-tech when Stelio Frati, master of the fluid curve, designed the Falco in 1955. The Falco's exquisite form and sparkling performance created quite a stir in Europe-enough of a stir, in fact, that 100 Falcos were sold as fully certificated factory-builts by Aviamilano, Aeromere and Laverda. It's the Falco's history that sets it apart from virtually all other homebuilts. The Falco is not an amateur design, but the certificated product of one of the most talented minds ever to direct its neurons toward crafting light airplanes. Thirty years ago, however, Frati was an idealistic 36-year old and once he was satisfied with the aerodynamic and structural design, the shop took over and the systems turned out to be rather a mess. For example: plumbing and wiring went through the firewall wherever a space presented itself; instead of using an angle drive, the tachometer cable passed through a tunnel in the forward fuel tank; and an area of the flap actuation used 50 parts where three now suffice.

In the eight years Scott has been working on the kit, simplification has been his overriding aim. The basis structure remains unchanged, and while it will never be known as the simplest homebuilt, the Falco is now within the reach of anyone with common sense and some woodworking experience. Karl Hansen had built model airplanes but never a full-size one, and he flew the Falco only one year, 11 months after starting the project.

Scott had originally intended to sell plans alone, not kits, but the more he polled the market, the more he heard, "Do it like the Christen Eagle kits. Give us everything." So he did. But in a departure from the Christensen formula, Scott lined up outside companies to make some of the kit components, including the wooden ones. This path was occasionally rocky until Scott came across one Francis Dahlman, whose Trimcraft Aero now makes all the wooden components to the extreme satisfaction of the kit builders. Karl Hansen, whose standards are nothing short of perfection, speaks highly of Dahlman's handiwork: "Boy, I'm telling you, that spar was a beautiful piece of work. So close to the plans-one millimeter out maybe."

Hansen's whole Falco is a stunningly beautiful piece of work. Most admirers refuse to believe it is made of wood. But wood it is, half spruce and half birch from behind the insulated stainless-steel firewall to tip of tail, and a credit to Hansen's meticulous attention to detail. The wing contours are literally as smooth as glass because Hansen spent two months profiling the ribs and spar caps before laying any skin. Rather than conceal, the paint serves only to protect and accentuate. When I flew the airplane, it had been out of the paint shop only a couple of days; its fiery hue acted like a red flower to bugs, which tumbled off the wings to the tarmac below, legs flailing, unable to gain a foothold on so slick a surface. Air molecules have an equally tough time holding on: Hansen's Falco slides through their grasp at 161 knots indicated (175 knots true) at 3,500 feet with 25 inches of manifold pressure and 2,500 rpm from its 160-hp Lycoming IO-320. At an economy setting of a miserly 5.25 gph, the airplane clocks 135 knots indicated (148 knots true). And there's more where that came from: as evident in the opening photograph here, Hansen still had work to do, notably on the nosewheel, which lacked doors and, through a misset actuation screwjack, protruded a couple of inches farther into the slipstream than it should have. One of the airplane's flaps was also slightly out of rig, calling for constant pressure on the stick.

You need not talk with Hansen long to appreciate his appetite for detail. A foray through his photo album of work in progress, from the first fuselage hoops to loading the airplane onto a flatbed in the driveway, clinches it. "The wing leading-edge wraparound was tricky," he'll say, "but we found a relatively simple way of keeping the skin in place while the glue dried. See those rubber strips? They're cut from a tire inner tube. It was still tricky though. Every time I hooked a strip over the nails in the jig, another would move"..."This is one of the scarf joints I was telling you about. I used a little sanding sheet for those and it really did a neat job"..."See the twist in the wing? The aileron trailing edge is 13 millimeters higher at the tip than at the root because of that twist" and so on with each turn of the page. After poring through the album I thought, "Sir, not only would I be at ease leaving Mother Earth in your handiwork, but I'd be honored to be invited aboard."

From the moment you step aboard, it's clear this is no ordinary airplane. It looks too well thought out to be a homebuilt and too near perfect to be a factory-built. Scott put much effort into designing a modern instrument panel, and he began by polling the market for what it wanted.

High-quality switches and warning lights are grouped in logical places, and nothing was "put there because there was a space for it." The airspeed indicator is twisted 90 degrees left of normal, so that the needle points straight up at the usual 80-knot approach speed (an arrangement that quickly seems quite natural). In addition to the usual ammeter, the Falco's panel also provides a voltage analyzer that shows how many amps or volts are being used or produced, for warning of any serious discrepancy between supply and demand. Hansen's panel holds two King KX 155 navcoms, a KN 64 DME (all new) and a used Narco AT150 transponder, in addition to an EGT, OAT, Hoskins HB-1 fuel-flow meter and Davtron timer-stopwatch. The Falco's seat belts and their mountings are stressed to 40 Gs, compared with the usual 9 Gs.

From the outset in June 1983, the Hansen Falco has been a family affair. On Karl and Shirley Hansen's fortieth wedding anniversary, one of their sons, Steve, showed them a Falco brochure and said, "If you build it, I'll buy it." There and then Steve, a doctor, produced a check for the plans. Karl Hansen began with the tail kit on a Ping-Pong table in the basement. He moved the project into the three-car garage when it was time to do the fuselage jigging and by Christmas 1983 he was ready for Francis Dahlman's main spar. The airplane was trucked out to the airport on July 7, 1985, and first flew 17 days later.

Hansen put in an average of 20 hours a week on the airplane for two years; at some stages he was working on it 10 hours a day. Son Steve did the instrument panel, and his first attempt was unsuccessful. After spraying it with matte-black paint and adding all the white lettering, he sprayed on a clear seal that caused the black to peel off. Second time around, he sprayed the panel with Plasti-Kote automotive sanding primer, redid the lettering and then sealed the whole thing with a Letraset scratchproof matte coating. The result is one of the best panels you will find in any light airplane.

Hansen opted for the more rakish Nustrini canopy, named after its originator, Luciano Nustrini, an Italian whose Falco has been timed in competition at 203 knots on 160 hp. Perennial victor of the Tour of Italy, he has won a bushel full of races in Europe since 1964. With the Nustrini canopy, headroom is adequate but not generous, a tolerable sacrifice for the cosmetic and performance improvements it brings.

If you mentally paint in a swept fin and a pair of tip tanks, you could be climbing aboard an SF.260, which is no surprise since Frati drew heavily on the form of the Falco when he sculpted the metal SF.260. Launching down the runway and heading for the heavens, the Falco could still be an SF.260-the 'quick as you think of it' response to control inputs, the sensation of cutting a very clean and short-lived hole in the atmosphere. But wait, what's this? The ailerons. They're lighter, a joy to play with. In fact, everything is a shade lighter than the SF.260. The Falco's rudder is particularly sensitive at cruise speed; a mere wiggle of the toe sends the nose skidding. Only the throaty rumble of a 260-hp six and the military aura of the SF.260 are missing. Other pilots have drawn the same conclusions and, according to Scott, some of the SF 260s in the U.S. were bought by people who fell for the Falco but not for the task of building one.

With Hansen and me and 192 pounds of fuel on board, the Falco weighed 1,763 pounds (117 pounds below max-takeoff weight) and climbed at 1,400 fpm indicated, in stark contrast to Alfred Scott's own Falco, a 1960 Aeromere-built example that I had flown a month earlier. Known as "The Corporate Disgrace," Scott's airplane has a 150 hp Lycoming with a coarse fixed pitch prop, making it the world's slowest Falco. A tired old airplane with some slop in the control circuits (slop that would go unnoticed on lesser designs), shabby paint and a generally lackluster air, it serves two important roles: Scott's personal steed, and a graphic contrast for the design before and after he had finished with it.

Hansen's Falco is a sheer delight to fly-crisply obedient, taut, not overly noisy-and, as merely a guest in the airplane, I tried to imagine the satisfaction he must derive from riding in a thoroughbred made with his own two hands. One look at the face of this happy filled in the details.

Frati gave the Falco its aerobatic prowess, but Scott has added modern long-distance travel to the menu. Even with the Nustrini canopy, the Falco would be a splendid way of moving about the countryside. Its Plexiglas acreage provides European visibility, and the slightly reclined seating position is relaxing.

Like the SF.260, the Falco descends sharply in the approach configuration when the power is pulled back. The flaps are effective, reducing airspeed by 20 knots when extended fully during a constant 500-fpm descent at a fixed power setting and the sensitivity of the elevators allows consistently satisfying touchdowns.

When the Hansens started building their Falco, they thought they might sell it one day, but with each flight that seems less likely. They have three other airplanes (Cessna 175, 210 and 320), and the Falco will replace the 210. What price would Karl ask if he decided to sell the Falco? "I might take $150,000. You don't want to put the price low enough that somebody will actually buy it."

Renaissance Architect

Before he'd even flown a Falco, Alfred Scott decided it was an airplane whose time had come-again, 30 years later; but this time as a homebuilt kit suitably updated and simplified. Alfred Scott had seen pictures of the Falco and heard the glowing reports that come from any pilot who's flown one. He felt that this moribund design had a promising future as a homebuilt kit-promising enough, in fact, that his company, Sequoia Aircraft, invested more than a million dollars in the project before he'd even seen a Falco in the flesh, let alone flown one. And what were his qualifications for the task of turning this 30-year-old design into a modern kit? Beyond a keen business mind and a respect for the airplane and its designer, not much, on the face of it. A University of Virginia liberal-arts graduate, Scott had logged stints as a stockbroker (with Merrill Lynch) and as a real-estate developer. He'd had a pilot's license since 1974, but his reputation as a bluegrass musician and bagpiper had spread farther through the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia than his reputation as a pilot. Revising the plans for the Falco and then making intelligible kits and manuals available would have been a formidable enough task for an engineer. For Scott it has been a Herculean job well done. His Falco plans, comprising 324 drawings and a 260-page instruction book that sell for $400, are widely considered to be the best plans on the homebuilt market. (Sequoia's brochures are also particularly slick and informative, and Scott puts out a detailed newsletter so that all builders can benefit from the others' learning curves.) Sequoia and Frati reached an agreement in March 1978, and the package that subsequently arrived in Richmond, Virginia, contained the original factory production drawings used by Aviamilano, Aeromere and Laverda. They were in Italian and unsuitable for homebuilders, so Scott set about redrawing them, writing the building instructions and generally putting the airplane's construction within the skill level of the average homebuilder. David Thurston, a respected name in light airplane design, did much of the redesign work, and Frati was kept in the loop throughout. Scott can see every cubic inch of the structure and every intricate detail with his eyes closed. Give him a paper napkin and a ballpoint pen and he's in his element, graphically explaining such prickly problems as the linkages, arcs and clearances for sequencing the gear doors properly (a refinement that most factory-built Falcos lacked). He expects his builders to follow the plans exactly; if they don't they will never buy another part from him, and they will not be allowed to call their airplane a Falco. If a builder tampers with a sound design and reaps grim consequences, Scott doesn't want the lawyers heading the Richmond, Virginia, base of his company. "I did it his way" is the one and only Falco anthem. The airframe, sold in 23 component kits, costs between $47 and $50,000 depending on options, and the builder has three choices of engine to buy: 150-hp Lycoming O-320, 160-hp Lycoming IO-320 or, for maximum takeoff and climb, a 180-hp Lycoming IO-360B. Scott prefers the 160-hp injected Lycoming (Karl Hansen's came from a Piper Twin Comanche). Despite his love for the Falco, Scott runs Sequoia Aircraft like a business, not the hobby of an enthusiast. His warehouse in Richmond is stocked with one million dollars' worth of kit parts-all fully paid for and ready to be shipped to the growing number of homebuilders who recognize that the Falco, far from being the nightmare from Milan, has become exactly what that dreamer in Richmond intended it to be. So far he's sold 420 sets of plans, and roughly half of the buyers are now building Falcos. Nigel Moll |

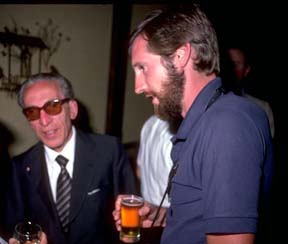

Stelio Frati and Nigel Moll at Oshkosh '85

|

|