The Versatile Syd Jensen

![]()

The Versatile Syd Jensen |

|

by John King

|

This article appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of New Zealand Sport Flying and was reprinted in the March 2003 issue of the Falco Builders Letter. |

Every now and then somebody comes along and makes a mark on a wide range of activities. Countless people put their stamp on a particular field, but only a few are prominent across a broad spectrum even in a country as small as New Zealand, and their names tend to live long after them.

Such a person was Syd Jensen, pilot, aircraft builder, businessman, engineer, racing driver and motorcyclist. Not only did he participate in all these varied activities, but he was also among the top in whatever he did.

"Syd didn't boast, but he knew how good he was, and he knew what he wanted to do," recalls Peter Stone. "He was a meticulous mechanic. His bikes and his workshops were all clean and gleaming."

One of the things the young Syd Jensen wanted to do was fly. His military career during World War 2 started in the army, but he transferred to the RNZAF and was ready to go to Canada for the advanced phase of his training when the war ended.

His father, Harold, had been a champion racing cyclist, but the young Syd had mechanical devices in mind for his sporting activities and bought a 1939 Triumph Tiger 100 road machine.

He rode it to victory in the first postwar meeting at Cust, against a large number of specialist racing motorbikes, which set the scene for his short career.

"He was an incredibly good rider," says Peter. "He had absolute determination."

|

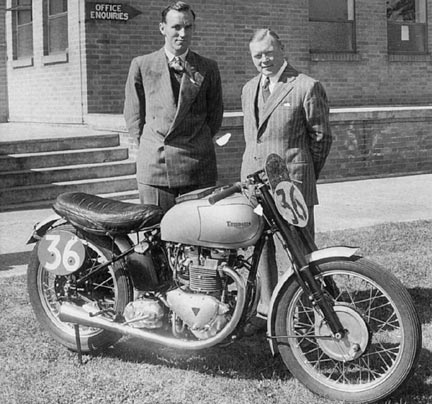

Syd Jensen (left) and Edward Turner at the Triumph motorcycle factory in Coventry. |

Such skills attracted the attention of the governing body, the Auto Cycle Union, which chose the young Syd to be part of the New Zealand team at the 1949 Isle of Man TT, the mecca of all motorbike racing. The arrangement was similar to the four-wheeled Driver to Europe scheme which resulted in the international careers of the likes of Chris Amon, Denny Hulme and Bruce McLaren but was long before the days of sponsorship. The NZACU raised money by subscription to pay for a promising rider's return fare to England and if he qualified for the appropriate TT race in a satisfactory time the UK ACU equivalent gave a further £100. Motorcycles to ride were the riders' responsibility, and they were expected to compete in the Continental circuit after the Isle of Man.

Syd Jensen traveled to Europe with his parents and Rod Coleman, a privateer who also made his mark on motorcycle racing and would win the 350cc IoM TT event two years later. The pair each rode an AJS 7R in the 1949 Junior TT, while Syd competed in the Senior TT on a Triumph GP500 loaned to him by the renowned Auckland motorcycle dealer Bill White. Syd's fifth place on the notorious sprung-hub Triumph was the highest achieved by any of that make up to that point, and a delighted Edward Turner of the Triumph factory asked Bill White if he would mind if they presented Syd with the bike.

For 1950 he was one of three riders, with John Dale and Jim Swarbrick, to represent New Zealand on behalf of the NZACU on the Island and the Continental racing. Again Syd went with his parents, but this time he also had his wife Jeanette with him. For his racing mount he chose a 500cc Triumph engine in a 7R frame, a combination approved by both factories as AJS was firmly in the 350cc class and Triumph was interested to see how its engine would go in a full duplex frame with acknowledged better handling.

But no good results came of it, and the summer of 1950 was not a good season for Syd. Back home, however, the bike had an exceptional record. "Nothing could touch it," says Peter Stone.

|

The combination of Syd Jensen and the AJS/Triumph, seen here at Oshakea in 1951, proved hard to beat. |

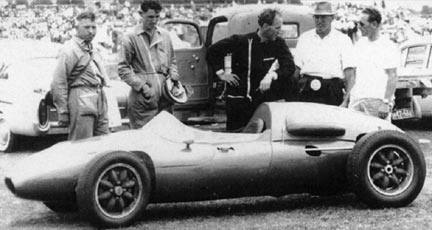

Having conquered motorcycle racing, Syd Jensen turned his attention to four wheels. In his first event, at Dunedin in 1953 in a 500cc JBS owned by Ron Frost, he achieved a worthy fifth place. Later progressing to a Mk VII Cooper powered by 498cc Norton, he finished sixth, the first New Zealander across the line, in the 1955 Grand Prix at Ardmore which was won by Prince Birabongse. Syd's was a notable effort as the little Formula 3 Cooper followed some fairly exotic heavy metal in the form of Ferraris and Maseratis, plus drivers of the caliber of Peter Whitehead and Jack Brabham, and he was third at Ohakea. In a Mk IX Cooper with 525cc Norton engine he was seventh in the 1956 Grand Prix, third at Dunedin, fifth at Wigram and second at Levin, the circuit he had promoted and built up with his father Harold, Ron Frost and others. An idea for a racing drivers' school at Levin never took hold.

|

Syd Jensen with the Cooper Climax at Ardmore in 1959. Syd came in seventh in this race which was won by Stirling Moss in a Maserati. |

Syd stayed with Coopers for his racing cars over the next few years. In 1956 he imported a Mk X from which he built another with a locally built chassis and some kitset parts, and in his hands it was actually more successful than the original. He also bought a Climax-engined T41 in England and later, accompanying Bruce McLaren back to England, put together a T45 Climax himself at the Cooper factory during 1958. Syd had some success with it, including a win at London's Crystal Palace, before shipping it home and doing well in local events, including a win at Levin. In 1960, after winning the Gold Star championship with a string of wins plus a fourth in the New Zealand Grand Prix, Syd sold the Cooper to Angus Hyslop who took it back to England with him as Driver to Europe and, for reasons of paperwork, officially had it built up to later specifications at the works.

Syd's business interests tended to reflect his sporting activi-ties. In his motorcycling days he ran a bike shop in Palmerston North, then owned a car sales and BMW import company, managed by somebody else, in the same city. Then he returned to aviation, having had his civil flying licence since 1947, and in 1956 started Aerocraft (NZ) Ltd, an aircraft maintenance company.

The Jensen family farmed on the outskirts of Palmerston North, and the Kairanga property of Syd and Jeanette sprouted a strip and Aerocraft's hangar, now the base of Hallet Griffin's Griffin Ag-Air. During the latter half of the 1950s Syd obtained a set of Druine Turbulent drawings from the PFA in England and proceeded to produce both complete aeroplanes and kitsets for local sale. ZK-BWE first flew on 8 December 1959.

|

Syd and a shiny new Druine Surbulent in December 1959. The airplane is still flying today in Whangarei. |

"He made three or four ready to fly, plus prefabricated parts for kitsets in New Zealand, including engines," says Peter Dyer. "I built the first kitset here, ZK-CAF, and was effectively his demonstration pilot in the South Island. Jim Muir, a Canberra pilot, would come over from Ohakea and flew BWE as the North Island demonstration pilot.

"Syd was an effervescent character, very positive in his ideas and very definite. He made a rattling good job of buying parts, but when dealing with amateurs he found it hard to recoup his costs."

There was a bit of friction on both sides. "Syd was trying to set up an organisation for ultralight aircraft, as they were then known," says Robin Hickman. "But he was more interested in selling his aircraft, so this was more of an owners club and not too much help for the homebuilder.

"One of his aircraft, ZK-CAG, I managed to beat in the heats at the air race at the opening of the new terminal building at Hamilton. His was all bright and shiny, and mine had a soft compression in one cylinder, but I had a slightly coarser prop so I had him in the straights. Rodney Hicks, the owner, was not happy about that."

Syd Jensen understandably, in the light of his experience with racing engines, concentrated on the engines, buying new VWs and modifying them with twin ignition and other Fittings. Aerocraft's woodworker was Dutchman Zeger van Klij who, according to all who knew his work, was a real craftsman who could make scarf joints by eye with absolute accuracy. As a new immigrant he also learned all the swear words first!

In the course of promoting his Turbulents, including strapping Tony Glowacki of the CAD into one at the first Paraparaumu fly-in, Syd flew ZK-BWE to many events. Neil Cribb, who worked for him in the early Acrocraft years, recalls a time when Syd returned home from Taupo, dodging cloud across the Rangipo Desert by closely following the Desert Road. His ground crew, less daring, was stuck in Taupo for days with a Tiger Moth.

But "the Turbulent idea was a bit ahead of its time," Neil thinks. "Syd went a bit cold on it. He would get enthusiastic about something, just get it going and then there'd be something else."

Acrocraft held its own as a business, maintaining general aviation aircraft and assembling the first Auster Agricola to be imported. By 1966 the company had grown to two bases, at Kairanga and the Aerial Farming hangar at Palmerston North airport, and was maintaining 30- - 40 fixed wing aircraft.

Some of those were Bölkow Juniors. sporting little two-seat trainers of which Aerocraft imported 10 in 1964. The first couple were completely built up by Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm in West Germany, while the rest were "green" airframes to be equipped, assembled and painted at Kairanga, with Rolls-Royce O-200 engines imported direct from England. The fleet is unusual in that all 10 are still flying almost 40 years later, a survival rate unmatched by any other type in New Zealand.

|

The Palmerston North Flying School's no 1 commerdial

pilot ground training |

The first example went to Middle Districts Aero Club, with others going to clubs and flying schools. Four Bölkow Juniors stayed on as Syd Jensen started the Palmerston North Flying School with Brian Milne as CFI and assistant Graham Leach. As well as the four Bölkows, the school operated a Rallye, 180 hp Sud Horizon, Cessna 180, 150 hp Super Cub and, yes, a Turbulent. The top Bolkow flew some 1200 hours a year.

Jim Evans joined Aerocraft after finishing his apprenticeship with Aerial Farming, and rose to become chief engineer. "Syd built the house at Kairanga using spruce beams as he'd bought spruce logs in bulk," he says. "Some was later cut up for aircraft construction, and we rebuilt an Aeronca Champ wing using the spruce for spars.

"He said he had one rule-never start a business and use your own name in its title, although both his motorcycle and car sales were named Syd Jensen. Over the years, working for different outfits, I found that he was my best employer. He was always fair and honest."

Part of that might have arisen from an experience Syd had in England, a story he often told. During his time readying a motorcycle for racing at the factory, all the workers knocked off for smoko, so Syd, wanting to get on with the job, used a welding plant to do some welding on his own machine. That nearly led to a major industrial dispute as he fell foul of the strict union demarcation found in all British labour at the time, and things were smoothed over only with difficulty.

Syd also started a Cassutt single-seat racing monoplane, but that project was sold unfinished. lie and Jeanette moved to Kerikeri in 1978, and it wasn't long before he started on another aircraft building project. Back in 1958 he'd had a ride in one of the early Stelio Frati-designed Falcos in Italy, and when kits became available from Sequoia Aircraft in Richmond, Virginia, he had to have one of these high-performance two-seaters and put in his order. Building started in May 1980, and with the help of Zeger van Klij again he was soon making such progress that it led to delivery problems.

As Sequoia president Alfred Scott tells it in the June 1990 Falco Builders Letter: "The progress he made in those early days was astonishing, even when you consider that he had a hired assistant. That was the time when we were best prepared to assist a slow builder, who took so long a-building that we had sufficient time to get the kits out. Syd and friend ripped through the basic woodwork in record time and would probably have been flying in 1983 if we had all of today's kits available then. But what actually happened was that Syd and friend ran us down and the project then entered a long and mutually frustrating wait-for-kit, install-it, wait-for-next-kit process.

"During this process Syd would take on odd business ven-tures of little subdivisions and these would take up a lot of his time. Syd could easily have flown in 1984, but he didn't rush the plane and then one sad day-literally as he was beginning taxi tests of the Falco-he found himself in the cardiac ward of the hospital. He didn't have a heart attack, but all of the alarms went off on the diagnostic machines. Syd had a triple bypass operation and within months was able to report that he felt better than he had for the past 20 years, but the New Zealand authorities considered bypass surgery as a ground-for-life event."

|

Lindsay Wheeler (right) is reacquainted with the Falco he helped build in Kerikeri, now owned by Giovanni Nustrini. |

Lindsay Wheeler helped in the project with fuselage frames, the canopy and wiring, and also helped install the engine, a Lycoming IO-360 with helicopter pistons for higher compression and more power. Falco ZK-TBD did fly, and Syd flew it to Taupo in 1990 (with backup pilot) when he and Jeanette moved there from Kerikeri. Peter Dyer, at the time also living in Taupo, flew it a few times and also demonstrated it to its second owner, Graham Hodge, who took it south to Canterbury and housed it at West Melton.

Enter the Italian connection. Luciano Nustrini obtained one of the first production Falcos from the factory in Italy and extensively modified it for racing, a big part of Italian aviation. I--ERNA had a lower windscreen and canopy and everything not really essential for flight stripped out, including the electric landing gear motor, headsets and intercom. The entire Nustrini family would pile into the back of the Falco and accompany Luciano and his wife Giuliana to race meetings. The house in Florence grew full of elegant silver trophies as the Falco was almost unbeatable, even as the handicaps grew ever more impossible as race organisers tried to counter its increased performance which grew close to 200 knots.

The Nustrini family moved to New Zealand, bringing I--ERNA with them and, after much bureaucratic wrangling, persuading the CAA that it was real, even if somewhat modified from the 1954 design, and registering it ZK-RNZ. They set up the local Tecnam agency and were active in promoting Italian/New Zealand relations, especially in yachting. Alas, Luciano and Giuliana died when their Falco hit the sea in February 1999 while farewelling a solo Italian sailor in the outer Hauraki Gulf.

Giovanni Nustrini then returned to New Zealand with his own family and continued the Tecnam agency with notable success, but all his life-and especially since learning to fly in 1983 with the Auckland Aero Club-he had wanted to own a Falco. ZK-TBD was the only other example in New Zealand, still owned by Graham Hodge but not seeing much flying, and it didn't take long for the ebullient Giovanni to persuade Graham to sell.

Earlier this year Giovanni and George Richards, nearing the end of his own Falco ZK-SMR project, flew airline to Christchurch, obtained type ratings and flew the Falco that Syd built back to Ardmore. Externally tidied up and painted yellow, and with some work on the engine, it now sits in the Tecnam hangar, ready to be taken out and flown at a moment's notice.

Syd Jensen died in July 1999, but his legacy remains. The Jensen

name is remembered in a wide range of activities-racing motorcycles

and cars, BMWs (from before they became commonplace), business

and aviation. The Turbulents may not have been the fastest things

around, but they helped set a homebuilding trend which is still

with us today and were followed by Bölkow Juniors and a special

Falco, one of the fastest two-seaters in the country and commemorating

the sporting side of its builder.

|

|