Hatching an English Hawk

![]()

Hatching an English Hawk |

|

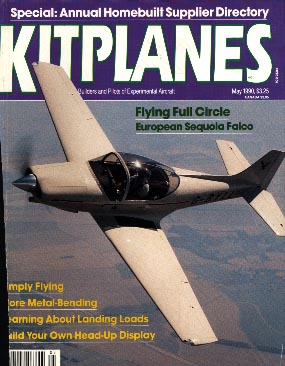

Was the first European-built Sequoia Falco

worth 5-1/2 years of work?

These Englishmen say yes!

by Geoffrey Jones

|

This article appeared in the May 1990 KITPLANES magazine. |

Knowing what he knows now after spending 5-1/2 years building his Sequoia Falco with two partners, Neville Langrick, a 42-year-old, self-employed chartered surveyor, admits that he probably wouldn't do it all over again -- that he'd prefer to buy a factory-built Falco. Not that he isn't enjoying the fruits of his long and hard labor these days; in fact, he claims the project was a fascinating challenge and probably the biggest achievement of his life.

If it sounds like this Falco was a real challenge and that only now are its builders able to realize that all of the problems and dilemmas they endured early on were worth it, you're right. How did Langrick and his two partners settle on the Sequoia Falco anyway? To find out, we have to follow the project back to its roots in the early 1980s.

Langrick, who lives near Huddersfield in Yorkshire, England, had been flying off and on for a few years when the Falco first caught his eye. One of only four Aviamilano-built F.8L Falcos operational in England at the time was based at nearby Crossland Moor Airport, high up in the Pennines above Huddersfield. After seeing it once, he knew he wanted to own and fly one of these "Ferraris of the air."

Bill Nattrass had spent seven years in the Royal Air Force as an airframe rigger before moving on to work as an engineer for David Brown Tractors. A neighbor and colleague of Langrick's, he also harbored a lifelong ambition to build his own airplane. When the two started talking seriously about embarking together on a homebuilt project, they decided it had to be a two-seater. They eventually narrowed their choices to the Falco and the Monnett Sonerai.

A few years earlier, Alfred Scott had formed the Sequoia Aircraft Corporation in Richmond, Virginia, to sell plans and kits for Stelio Frati's fighterlike, all-wood, two-seater, the Falco (Hawk). The United Kingdom representative for the Falco was Doncaster Sailplane Service in Doncaster, which happened to be only an hour's drive from Huddersfield. A copy of the Falco information brochure was the final persuasion Langrick and Nattrass needed. Without even talking to anyone else who already had experience with the Falco, they ordered the plans direct from Sequoia in the U.S.

Although there wasn't a complete builder's manual when they took delivery of the plans (there is now a very comprehensive one available), both Langrick and Nattrass have the highest praise for the plans and drawings. They suspect that they've been completely redrawn (and translated) by Sequoia from the Italian originals. Despite a few idiosyncrasies in the drawings of some of the smaller hardware items, where there was a confusing mix of U.S. and metric measurements, they feel that even an inexperienced builder should be able work from the plans without any trouble.

On a shopping trip to Doncaster Sailplane Service in November, 1982, the pair picked up the spruce for the tailplane rib kit. Because they were first-time builders, they bought the cheapest wood available so that they wouldn't feel too embarrassed if building the Falco turned out to be a disaster and they had to throw the whole thing out. Fortunately, that never happened.

Working in their respective homes, Langrick and Nattrass found that the number of airframe parts was multiplying rapidly. After six months, they had a large number of the wooden assemblies, including spars (not the main spar yet) and fuselage and tail sections. It was time to think about a larger workplace where they could start putting the pieces together. As Langrick had a 20 x 20-foot double garage that was well stocked, had central heating and lighting and was a sociable outpost as far as family and friends were concerned, the Falco was moved there.

Initial assembly of the plane was quick, including the fuselage, which is actually built in one piece, then cut in half! That's how Falcos were made at the plant in Italy and it is a major advantage of the design for homebuilders who are tight for space. The cut is made at fuselage station 8, just behind the cockpit. There is a small gap between the two sections, which remain only loosely joined while the fuselage is being skinned. They are later connected tightly by 12 bolts.

Even the Langrick family garage wasn't big enough to accommodate the one-piece Falco wing, which spans 26 feet 3 inches, so a specially built shed was put up in the garden. It was 28 feet long and had just enough headroom to allow Langrick and Nattrass to begin working on the main spar and wing.

They built a long, flat table and acquired dozens of joiner's clamps with which to build the laminated main box spar. The wing itself was built in a vertical position with the main spar suspended on jigs and the ribs fitted in place from the center outward. The single main spar runs from wingtip to wingtip, while the aft spars are separate and only as long as each wing half. Although the wing ribs are made in one piece, like the fuselage, they have to be cut up to be glued onto the forwardand rear-facing surfaces of the spars. Construction of the wing took about three months, excluding skinning.

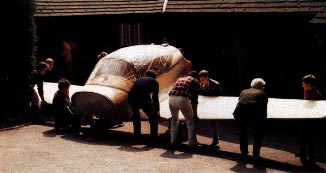

When it came time to mate the wing to the fuselage, a T-shaped extension to the "garden hangar" was required. Although the fuselage is designed to be cut and, in fact, was cut soon after, it is necessary to have the airframe in one piece while making triangulation and dimensional checks on the wing and fuselage. The Falco construction manual now available from Sequoia recommends the builder have a large workshop, but Langrick and Nattrass were breaking new ground with their learn-as-you-go project back in 1983.

After 18 months, their pieces and parts were finally starting to resemble an airplane. It was a good thing, as inspiration and enthusiasm were beginning to wane at that point.

The cockpit area of the fuselage and wing center section were set on trestles in the workshop for installation of the flaps and ailerons, which were built directly onto the wing. This was considered the best way to go because the washout and dihedral of the wing is carried through in the shape of the control surfaces. This was one of the most difficult aspects of the project, again because they were breaking new ground.

At this point in the construction, the builders' thoughts began wandering to the engine installation. Intending to do their own rebuild under the guidance of the Popular Flying Association (the British version of the EAA), they bought a 150 hp Lycoming 0-320-A3C from a French Sud Aviation GY-80 Horizon, a lightplane they discovered was being parted out by Yorkshire Light Aircraft.

Langrick and Nattrass soon abandoned the self-rebuilding idea and opted to buy a new engine instead. But that idea, too, came to naught, so they ended up shipping their engine to Standard Aero in Canada for a complete rebuild. In retrospect, they believe that purchasing a new engine would have been the best way to go. They would also have opted for a fuel-injected engine rather than a carbureted one because Sequoia provides a bottom cowling kit that has to be radically modif~ed to accommodate the carburetor bays and air intake.

At this stage of the project, even though the airframe was nearly complete, the number of minor details that inevitably turned into major tasks seemed to be growing daily and pushing the completion date further and further from view. These were trying times for the beleaguered builders.

Langrick has nothing but praise for the support, both moral and practical, provided by Nattrass during these dark hours. Nattrass had a small Myford lathe at his workshop, and since day one, he had turned out a multitude of beautifully machined metal parts and fittings, including hinges, bellcranks, pulleys, control column hardware and the rudder bar.

It is here that Langrick feels a lot of homebuilders are misled. "Many kit manufacturers claim their aircraft can be built by the 'average' craftsman," he says. "I truly believe that had it not been for Bill's skill gained from a lifetime of experience as an engineer, our Falco project would have foundered. My only experience prior to starting this project was reaching the 'Advanced' level of woodworking in grammar school. This had taught me the basics about tools and materials, but an undertaking like this -- building your own aircraft -- is a whole new ball game.

"For example, there's the gluing and bending, which is quite difficult and requires considerable self-discipline to learn -- it's like serving an apprenticeship. Even if a complete Falco kit had arrived in a big box with the spars and all the other major components already fabricated, construction would still have been a daunting task. "

All of Natrass' engineering skills came to the fore when he was working on the main gear and retraction system. Getting it to fit correctly into the fuselage/wing module was, he insists, probably the most difficult part of the building project. You may be thinking that this shouldn't have been so tough, but remember, this Falco was built from scratch from plans, not from a kit!

The nosewheel landing gear leg was bought already completed from Sequoia in the U.S. because its cast-aluminum construction would have been nearly impossible for them to duplicate affordably. In fact, just getting it X-rayed in England would have cost more than the shipping charges for the one they had shipped from Sequoia.

Once the gear was fitted and the Falco could stand on its own feet, Langrick and Nattrass were finally able to enjoy a well deserved moment of satisfaction and motivation from their achievement. As men of modest means who were fliers first and builders second, it was at this point that they decided to invite a third person to join their team. Ray Holt, a land drainage contractor and keen sport pilot, happened to share Langrick's and Nattrass' passion for the Falco design. His addition to the team provided a much needed injection of cash into the proceedings, enabling them to purchase from Sequoia such necessary items as the canopy and canopy frame, nosegear, engine mounts and other parts that were nearly impossible to make or obtain in England.

At that time, Langrick pointed out, Sequoia was anxious to sell builders any parts and components they wanted for their Falcos. Possibly to avoid potential problems with product liability claims, that situation has changed, and now, only full or component kits are available. But Sequoia now produces and sells kits for each of the all-wood components for the Falco, such as the wing spars and fuselage frames. The Sequoia inventory of available Falco kits now numbers 29, eliminating much of the heartache this trio of Englishmen had to endure to scratch build their Falco.

Another of the more frustrating parts of the project was positioning the canopy to fit. It was all a matter of trial and error because both the canopy and frame moved around a good bit. There seems to be no trick to getting it right, except maybe persistence and a great deal of patience.

Because Holt had a workshop big enough to house the assembled aircraft, the Falco was moved there for final assembly. After building the fiberglass seats, the first major task was to turn the plane upside down and begin the six-month process of finishing the undersides of all the surfaces for painting. Holt was also responsible for the upholstery, avionics and painting. It's interesting that during the last 18 months of the project, each of the three builders was occupied with his own particular tasks, and there was very little discussion between them.

As inexperienced builders, they never really considered the

concept of weightsavings until almost the end of the project.

In self-defense, they claim that if they erred at all, it was

on the side of safety -- using sufficient rather than skimpy quantities

of glue, and cutting wood just outside the pencil line rather

than exactly on it. In retrospect, they would like to have been

more attentive to saving weight where they could, but they note

that in that respect, the Falco is considerably more tolerant

than many other designs.

The matter of weight and aircraft performance led Langrick, Nattrass

and Holt to question the impression fostered by some kitplane

manufacturers -- including, to some extent, Sequoia -- that "a

sport airplane is all things for all men." Quoted weights

and performance figures don't always stack up the same for every

flying situation. For example, you can't fly two people, baggage

for a weekend stay, cross-country fuel, autopilot and full avionics

and still be able to do aerobatics.

Still on the nagging subject of aircraft weight, Langrick questions the recommendation by some alleged homebuilt experts that you can use bathroom scales to weigh an airplane. He thinks it is a definite no-no and instead recommends doing what he did with the Falco: have it weighed professionally with electronic scales.

Though they were nervous about it possibly being overweight, the LangrickNattrass-Holt Falco weighed in at 1293 pounds, 15 pounds heavier than one factory-built Falco, yet several pounds lighter than another weighed by the same company. The difference, as it turned out, was mainly due to the lack of avionics in the factory-built models. Langrick breathed a sigh of relief, but is still amazed at the light weight of some of the Falcos built in the U.S.

In addition to the gear and canopy, fitting the seats and seat tracks proved to be a troublesome chore. The tracks are made from lightweight material, and for the seats to slide back and forth smoothly, the tracks have to be exactly parallel. While being tightened, they had a tendency to move, making it an extremely frustrating job to get right.

Except for the avionics, all instruments were bought new, some being specially calibrated for the Falco. These all-new instruments later caused monumental headaches and the majority of the teething problems once the Falco finally flew. The directional indicator, front fuel tank gauge and altimeter -- which arrived with one of the needles Iying loose behind the glass face! -- were all faulty.

Installing the instruments and electrical wiring was the responsibility of Langrick, who, though he is no electrician, found the job enjoyable and relatively easy, thanks to Sequoia's excellent drawings and color-coding that made any mistakes easy to spot. Another reason he enjoyed the work was that much of it could be done in the comfort of his lounge at home by setting the instrument panel face up on a table and working from there.

Preparation for painting began toward the end of 1987 with the tedious process of rubbing down, filling and undercoating. A twin-pack epoxy paint, applied by a professional auto sprayer, was used for the final coat on the Falco, which was again split into two sections for the task. The color is a 1965 General Motors light beige, which sounds kind of dull, but actually looks very classy.

For final assembly, the Falco was trailered to Sherburn-in-Elmet, an airfield east of Leeds, West Yorkshire. Langrick, Nattrass and Holt expected to spend a month getting it flightready -- it took six months! Soon after the airplane arrived at Sherburn, the project received a severe blow when Nattrass suffered a heart attack and a stroke. Because the trio had not conferred much during the past year and a half, the parts of the Falco Nattrass had been working on at home were a mystery to the others.

Nattrass suffered a speech loss as a result of the stroke, but as soon as he was well enough to accept visitors, Langrick visited him in the hospital with the mysterious bits and pieces he'd been working on, and through a process of sign language and lip-reading, learned what each piece was and where it went on the Falco. After a few months, Nattrass recovered enough to be discharged from the hospital. During the final weeks of preflight checks on the plane, he was able to join his partners at Sherburn to provide his valuable assistance.

June 6, 1988, dawned still and sunny at Sherburn airfield, and saw Langrick, Nattrass and lIolt wheeling their Falco out of the hangar for its first flight. In honor of the effort and inspiration provided by Bill Nattrass throughout the project, even after he had been struck down by the heart attack, the Falco was registered with the British CAA as G-BYLL. It was a touching tribute.

Sequoia's Alfred Scott stressed it and the three Englishmen endorsed it: Even if you are a pilot and you did spend the last 5 - 1/2 years building the airplane, that doesn't necessarily qualify you to be the test pilot, especially on a relatively "hot" plane like the Falco. For that reason, the fourth person at the airfield that morning was the test pilot for the Falco's first flight, "Jacko" Jackson, who was the CFI at the Sherburn airfield flying club and an ex-commanding officer of the RAF Battle of Britain Memorial Flight.

As "Jacko" lifted the Falco off Sherburn's grass runway for the first time, an odd feeling of apprehension overwhelmed the three ground-bound builders who were watching the event. Finally seeing the fruit of their labors take flight was an emotional experience. When G-BYLL landed, their apprehension turned to relief and then elation. It was a private and fulfilling moment, to say the least.

The relatively short first flight, during which the gear was left down, was nearly perfect, except for a heavy left wing, which was corrected by fitting a trim tab to the right aileron. The 6 hours of test flying required by the PFA for the aircraft to qualify for a Permit to Fly were flown off over the next two weeks. But the builders were dealt one last disappointing hurdle when the PFA was unable to process the paperwork quickly enough for the Falco to be flown to the 1988 PFA International Rally at Cranfield -- the "big one" for sport aviation enthusiasts in Europe -- at the beginning of July.

In August, Langrick finally got his hands on the Falco for his first solo flight. He now admits to considerable trepidation about it. But his fears again turned to elation once he landed safely. The Falco was different from everything else he'd flown previously. It was beautifully stable and easy to handle in cruise, holding a heading extremely well, but was quite a handful for a novice in the pattern. Approaches are normally flown at 80 mph, slowing to 73 mph over the threshold. Stall speed in the "clean" configuration is 59 mph.

By late 1989 the Falco had clocked 125 hours of flying. Several experienced homebuilders who had built and flown airplanes similar to the Falco advised that it would take about 100 hours to sort out the teething problems that were typical of such a high-performance homebuilt. Their estimates were right on the mark. The instruments were a major headache, as was the air intake under the cowling, which was too small and had to be enlarged, because at full rpm, the engine was starving for air. That was the only modification required, and the owners report that their strictly-to-plans Falco has proven to be all that Sequoia Aircraft promised.

A large portion of the Falco's air time was put on by Holt when he made the 3000-mile flight to attend the Malta International Air Rally, where the plane won the Concours d'Elegance trophy. This first long trip was an opportunity to really evaluate the Falco's performance. During earlier short hops, the engine was burning 10 gallons of fuel per hour. On the Malta flight, at 7000 feet and 75~o power (2350 rpm), the rebuilt 150-hp Lycoming settled down to a fuel consumption rate of 9.3 gph and burned only 2.5 quarts of oil. Cruise speed was a very satisfactory 141 mph.

An interesting phenomenon that occurred during the trip to Malta was that the Falco's wing ribs became visible through the skin. As they became invisible again back in England, the change was attributed to the hot Mediterranean climate.

When asked the usual questions about how long it took and how much it cost to build their airplane, Langrick does not have a ready reply. "I honestly don't have a clue about how many hours it took to build, " he said with a shrug. "Bill Nattrass retired from his job at David Brown Tractors during the first year of construction and worked almost full time on the Falco-he certainly averaged at least 5 hours per day. I had two years of work myself. Ensuring that all the component bits came together fast enough to keep up a reasonable time schedule on the main assembly of the aircraft became a fulltime occupation for both of us. There's the time Ray Holt put in, plus the time spent by subcontractors like Standard Aero on the engine, the paint sprayers.... It's inestimable.

"Cost is slightly easier to assess. As far as I'm concerned personally, the project was a heavy financial burden. It hurt a lot at the time, but now that it's done and time has passed, it doesn't seem so bad. It was still a relief to be finished, though. Very roughly, we estimate the Falco cost £45,000 (about $78,700 at the current exchange rate). We'd be very interested to hear what other builders have spent on their airplanes. But our costs were undoubtedly inflated by having to pay UK import duty, value-added tax, shipping charges and the like."

Looking back on all their trials and tribulations, Langrick thinks that any disciplined Falco builder working on his own could expect to spend around 10 years on a plans-built version, maybe less, depending on how much work was sub-contracted. He could not credit Nattrass enough; his technical experience and rigorous work routine were essential in seeing the project through.

And what of domestic and social life during the project? Langrick was and still remains a married man with a family. His declaration that he will never again get involved with a homebuilt aircraft project tells a lot about the sacrifices he had to make in that area. It was his experience that the further along the project got, the more he tended to develop a kind of tunnel vision in which the airplane became the overriding interest in life, to the exclusion of almost everything else The only consolation for wives in that predicament is that they know where their husbands are -- in the workshop!

When they flew the Falco to 1989's PFA rally at Cranfield, it was awarded the ultimate accolade: the Air Squadron Trophy for Best Homebuilt. Though Nattrass was still not flightready after his heart attack, he was the first person Langrick and Holt telephoned the moment the awards were announced. Then and there, the three friends were finally sure that G-BYLL was worth the effort after all.

|

|