![]()

Building N98KM

![]()

|

|

Building N98KM |

|

by Kim L. Mitchell

|

This article appeared in the December 1998 issue of Falco Builders Letter. |

As president of a small electronics manufacturing company in Oklahoma, I have for many years enjoyed the luxury of a company airplane, available almost anytime it's been needed. But at the beginning of 1991, I started thinking about the need for an airplane when I retire. Retirement was in the distant future, but I like to plan ahead. Also, my job was becoming more and more stressful, since I was spending less time doing enjoyable work (engineering) and more time doing what was needed (management). It was time for a relaxing hobby. These two things led me to consider starting a homebuilt airplane project.

I looked at all of the kits available at the time. The Falco rose to the top of the list for a couple of reasons. Woodworking has always appealed to me, but there has been very little opportunity to do it over the years. I still remember having to give up shop class in high school in order to take chemistry and physics. Also, I wanted a fast airplane, and it seemed the Falco was the fastest wood airplane available. The Falco kit had the reputation of being relatively labor intensive but, what the heck, I had plenty of time till retirement, and I felt I needed the distraction. Surely this thing would not need more than four or five years to complete.

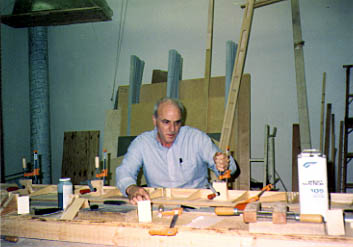

Kim early in the construction process.

Such a large commitment of time and money caused me to agonize over the decision for several months. The feelings of the spouse must be taken into consideration. My wife earned her private pilot license in 1975, but she had since lost interest in aviation. So she did not share my enthusiasm for the project. She understood the large amount of time the project would keep me away from home, and so was only mildly supportive. At least she did not exercise her veto power. I appreciate the fact that she has accepted the situation without complaint.

On a trip to Florida in February of that year, we visited Ralph and Judy Braswell in Ocala and looked at his Falco project. The obvious quality of his work was intimidating. Could I do work this good? Was such precise workmanship necessary? I later learned that a lot of sanding can compensate for some kinds of imprecision. On the way home we stopped in Conway, Arkansas, where a local lawyer gave me a ride in a Falco which he said had been built by someone in Pennsylvania.

This experience demonstrated what a delight the Falco is to fly. Up to that time, I had only flown Cessnas and Pipers with their heavy controls and slow responses. Still not completely convinced, I visited Howard and Marty Benham in Wichita, Kansas, to see their project. Once again the beautiful construction was impressive. Howard answered enough of my questions to convince me to take the plunge.

So, where to build it? There was no good place at home. The garage was full of cars, and it would have been too small anyway. My company had a little-used garage that seemed ideal-heated and air-conditioned (very important in Oklahoma), high ceiling, and 12' x 12' door. Just a one-minute walk from my office. I could play with the project an hour before work, during lunch and coffee breaks, and an hour after quitting time. This, combined with weekends, would allow me to devote about 25 hours a week to the project without seriously disrupting family life. I could still take business calls and handle urgent problems when necessary.

As it turns out, I averaged about 10 hours a week logged time and probably one-fourth that much unlogged time. But that includes the one year I waited for Sequoia to make their first wing ribs, and the many months I was out of the country.

I bought a radial saw, grinder, belt sander, and battery powered drill. I borrowed a bandsaw, drill press, and jig saw. These, together with all the normal hand tools, turned out to be all that was needed. Actually, the only time the radial saw seemed more a necessity than convenience was when making the angle cut on the end of the aft wing spar. The band saw was most useful, followed by the drill press. I tried to use hand tools whenever possible, instead of power tools. This took longer, of course, but minimized the possibility of catastrophic mistakes, and provided a more pleasant experience. The process of bending birch plywood was very pleasant. In my travels I have become a great fan of the Russian banya (steam bath), and the heat, steam, and smells of birch plywood bending reminded me of that.

I soon learned to heed the warning "Don't try to visualize the whole airplane at once-that's too intimidating and confusing. Concentrate on one task at a time, making sure it is done correctly, and have faith that everything will come together properly." Good advice. But this approach caused the means to become the end. The construction process became so enjoyable and satisfying, impatient expectations of a finished product were forgotten.

It was interesting to see the reactions of people who visited the workshop. They were pretty consistent. During the first few years people were amazed by how little I had to show for so much effort. Just a few bits and pieces here and there in that big garage. Later on, after the fuselage was built onto the wing, they would look at the airplane, then look at the door, then say "How you gonna get this thing out of here?" I would say "Oh my God, why didn't I think of that? Guess I'll have to cut it in two." Great fun.

I was on a work-study program in St. Petersburg, Russia when Howard Benham's Falco was totaled. Upon returning home and finally hearing about it I first thought, what a tragic loss of time, effort, and money. But eventually I realized that if the same thing happens to me, I will have no regrets. The satisfaction of successfully completing such a monumental task justifies everything. In the meantime, it's just now beginning to sink in that I have a beautiful, fast, and extremely capable cross-country and aerobatic flying machine.

I was fortunate to have a lot of good help. Alfred was always available to answer questions and find ways to bail me out of stupid mistakes. Two skilled machinists in my company, who have been totally enthusiastic about the project, helped solve many problems. No provision for a cabin air inlet valve in the plans? No problem. Just ask Alfred to fax a sketch of something that will work, give the sketch to Bill and Lonnie, and voila, in a couple of days a finished part appears. Another employee, a pilot, instructor, shade-tree airplane mechanic, and deep thinker, provided much useful advice and helped with two-man jobs. Mike also provided moral support when things got tough. Don't hesitate to seek out such help. It makes the project easier and more fun.

Speaking of getting help, when my plane received FAA certification I came to the embarassing realization that here was an airplane I could not fly. I'm not exactly an ace pilot and have always had trouble transitioning from one airplane to another, especially one as different as the Falco. Jim Petty, a Falco builder in Oklahoma City, came to the rescue and gave me instruction in his outstanding bird, N627SF. I was a little demoralized by comparing his attention to detail to my lack thereof, until he explained that he has had a few years to refine his airplane. Seeing Jim's plane brought home the fact that the project is never really finished. Gear doors need to be built and installed, paint touched up, alternate air added, and on and on. I find this comforting, because I hated to see such enjoyable activity come to an end.

Finally, Howard Benham had enough confidence in my construction skill (or maybe in his flying skill) to make the first flight in N98KM. We started trying to do the first flight as soon as the plane was certified in late September. All through October, every time Howard had a day off, the weather was lousy. Then, for all of November, I was out of the country. I'm told the weather was perfect all the time I was gone. This was becoming frustrating.

Finally, on December 13, everything came together. Howard was off work, the weather was good, and I was here. Howard and Marty left Wichita in their 180 at the crack of dawn (not all that early, this time of year). Howard had carefully inspected the Falco on a previous aborted attempt, so only a quick preflight was needed now. He took out the seat cushion and put on his parachute. The engine started easily, and Howard taxied out to do high-speed taxi tests.

Everything looked okay to me, but soon he was back at the hangar. Run-up had shown two fouled plugs, the result of too much ground idling of the engine. Thanks to the engine analyzer I had installed, these plugs were easily identified and quickly replaced. Soon Howard was off again. He took off as if it were an everyday occurance.

I jumped in the chase plane, together with Marty and Lonnie, and taxied to the active. Meanwhile, Howard was flying the pattern and overflying the runway. Everything must have been okay, because he departed the pattern to the practice area northeast of town. I took off in the chase plane and tried to catch him. This was not easy. He was climbing at 1000 fpm gear down and making pretty good forward speed, too. Encouraging.

Howard did a lot of different stalls. One of them must have been an accelerated stall and resulted in a 90 degree wing-over. I thought for a moment he had lost it, but everything was fine. An inconsiderate local politician, who happened to be on frequency, tried to carry on a conversation with Howard during this test flight, but Howard handled it well.

Finally coming in for landing, he flew well past the runway on an extended downwind, and once again I thought something had gone wrong with the airplane. But it turned out he was just avoiding a flock of birds. Seeing that Falco fly, up close in a chase plane, was both thrilling and nerve-wracking. Howard remained very calm through the whole process, but I can't say the same about myself.

N98KM weighed in at 1277 pounds empty, with the CG at 66.87 inches. Adding the gear doors will change these numbers a little. Logged construction time is currently 3,500 hours and unlogged time (time for planning, shopping, discussing, etc.) is another 800 or so hours. Equipment includes Garmin GNC 250 GPS-Com, King KX-165 NAV-Com, King KT-76A transponder, PS Engineering PM2000 intercom, GEM-610 engine analyzer, Electronics International FP-5 fuel totalizer, Davtron 301 OAT, Precise Flight alternate vacuum system, and Century I autopilot. I plan to use the airplane IFR, but I will not do so unless the autopilot is working perfectly. I have become accustomed to Stormscopes in our company planes, and I will sorely miss this super useful device. I will also miss having an HSI, but maybe a GPS pseudo-HSI will help fill this gap.

What's the hardest part of the Falco to build? Someone mentioned in a builder's letter that the flap-ailerons were hardest, and I agree. After carefully assembling the ribs to the spar with precisely the right amount of warp, I then laid the assembly on a flat table to glue on the skin, thus losing part of the warp. I also varnished the inside surfaces with the trailing edge down, so that varnish migrated toward the trailing edge, aggrevating the control surface balance problem. Another thing that was difficult for me was leveling and squaring the wing to the fuselage. I spent two weeks doing this. Another hard job was fitting the front fuel tank in the fuselage.

The most exciting event of the construction process was when my radial arm saw kicked back a small spruce stick, sending it flying across the workshop and completely through the vertical stabilizer (at the exact location of the com antenna, naturally). Maybe this experience explains my aversion to power tools. Fortunately, wooden structures are relatively easy to repair.

Difficulties are inevitable in such a project as the Falco. I think the key to successful completion is to address problems as they occur, before moving on to the next step. For me, the process and the result were both worth the effort.

|

|