Building a Falco,

Part 3

![]()

Building a Falco,

|

|

by Stephan Wilkinson

This article appeared in the January 1990 issue of Pilot magazine in England.

The fuselage had to be sawn in half (it was designed to be) to fit out the door of the barn.

My Falco is nearly finished. That is a neat description that allows latitude for everything from truth to fantasy, as so often do the timetables of homebuilders. When curious friends inquire after my progress, I invariably say, "Oh, it's standin' on the gear, cockpit's finished, looks like an airplane." (At least it did until I sawed it apart.) I explain that the Falco has reached a state that would allow any real homebuilder to have it flyable in a month. The engine needs to be hung, the instruments and avionics are yet to be plugged into the panel, some plumbing awaits, and there's a week's worth of woodworking still to be done, for the airplane's private parts-belly and groin-have so far been left naked more easily to allow the installation of wiring and internal systems.

Yes, I'm aware of the commandment that "firewall forward is half the work." But the Falco's engine is a proven installation done often enough-and with subkits sophisticated enough-that placing an IO-360 on the motor mount, cowling it and hooking up the plumbing and electrics is said to be a week's part-time work, once I figure out how to lift the fool thing. I fear that any hoisting technique that depends on the integrity of my barn's beams will result in the barn descending to the level of the Lycoming rather than elevating the engine.

My airframe, at least, is complete. The wiring harnesses are all in place. The cockpit is carpeted and upholstered, though all the fancy stuff has been stored for safekeeping. The structure is nearly ready to accept paint. The landing gear motors up and down. The control surfaces obediently waggle and flip. And if God is in the details, He awaits first flight in carefully crafted cockpit ventilators, fiberglass control-horn fairings at every conceivable location, Connolly hide on glareshield and baggage-compartment turtledeck, artfully Dzus-fastenered access doors and panels at all the necessary locations.

But I know that I can stretch this job out for another year, maybe two. I tell myself that one of the dangers of homebuilding airplanes too hastily is that the anxious pilot-builder intends to finish all the messy details sometime after first flight and never does.

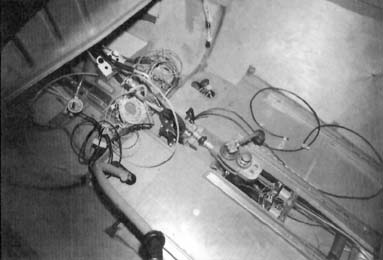

In at least one regard, I'll fall into that trap myself, for I've seen how chipped and battered nicely painted cockpit components become as work progresses around them. At this point, the cockpit is a Medusa's head of unconnected wiring, tubing, piping, cabling and controls, most of it writhing up through a pair of holes in the floorboards to terminate somewhere behind the panel. Some also snakes back from the firewall, and my main fear is that when I hook everything up, fuel will pour from the pitot tube, the oil cooler will receive glideslope signals, the manifold-pressure gauge will wigwag like a VOR, the brakes will lock when I key the mike and the control stick will be as electrified as as cattle prod.

So I intend to fly the airplane with the instrument panel and power pedestal still unpainted. Then, after I've had the panel in and out a dozen times to find the inevitable reversed wires, loose connections, leaking hoses and inop systems... then I'll take it home, take it apart, and give it a beauty treatment.

Falco parts have also invaded the author's tiny studio office, making access to the word processor tricky.

Falco builders seem to find their way into one of two groups, and I long ago chose mine. The airplane has a reputation for complexity and endless build time, especially in this era of instant aeronautical gratification. ("You simply glue the two halves together using household detergent as a solvent for the polyvinylexcrement, plug the propshaft into the proven lawnmower engine we supply, cut an access door wherever you wish with an ordinary hardware-store keyhole saw, climb in and go fly!) So certain Falco builders set out to disavow this difficulty. One Chicago builder completed a Falco in 11 months, though he needed to import two devoted woodworkers from his native Poland in order to do so. Others have done it in less than two years of part-time work, and certainly the Italians who factory-built certificated Falcos for Aviamilano, Aeromere and Laverda (sounds like a firm of Roman divorce lawyers, doesn't it?) did it in jig-time, no pun intended.

The "bit that looks like a one-sixth scale Malibu wing" is the elevator.

I, however, am delighted to spend an entire afternoon fitting, sawing, chamfering, sanding, tapping and smoothing a single small block of wood that will be used as a post for a battery-cable hold-down fitting, say. I'm happy to spend an evening seeing to the routing of a single brake line, trying alternate paths, checking the location of clamps, swinging the gear to see what happens to the flexible tubing as the wheels retract. I look forward to burning up a day crawling into the tiniest part of the tailcone like a mad mole to install the marker-beacon antenna that I forgot to fit back when the area was more accessible, then fiberglassing the cable juncture solidly into place and finally varnishing everything down, drunk from the polyurethane fumes in my little plywood cave.

I have had my doubts about building a wooden airplane. First when my young daughter refused to contemplate flying in anything held together with glue, which she knew as the ingredient of kindergarten constructions. Most recently when I sat with a former president of the Grumman Corporation, interviewing him for a film I was writing.

Hoping to establish some bond as an airman with this lofty figure who happened to also be a pilot, I told tough old George Skurla that I was building a spruce airplane called a Falco. His nose wrinkled with disdain. "Jeez, a buddy and I bought an old Fairchild awhile ago-what was it? A PT-26, I think-and boy, lemme tell ya, we got into the wings and that thing was all rotted," he said in a rich Long Island accent. "You don't wanna mess with wood airplanes." Granted, this was the man who made Tomcats and Lunar Modules, but I wondered. (I also wondered how rich you have to be to buy a classic airplane and not be entirely sure of its type.)

But today I have finally finished dealing with the one substantial area of aluminum on the Falco-the canopy skirt and windscreen trim strips-and I have nothing but pity for hand-builders of metal airplanes. My hands are blistered and nicked, sliced and splintered, bloodied and aching. Aluminum is an initially yielding material-how nice that you can cut it with scissors, you first think-that turns obstinate and dangerous as those very tinsnips convert it to a huge razor. It is soft enough to sand yet hard enough to pierce gloves.

My Falco-ing is a rather haphazard process, as typified by the fact that I haven't yet any good answer to the inevitable question, "How will you get it out of the barn and to the airport?" Nor do I have an answer to the question, "What color will it be?" There are some builders who know nothing about their airplane but what color it will be, and many seem to expend more effort on the design of a paint scheme and interior than any other part of the airplane.

Having never seen a truly beautiful Mercedes, Rolls, Ferrari or Porsche with feathers, hawks, cheetahs, stripes, speed lines, zoom stripes or any other ornamentation, I think I'll paint my Falco a single, solid, unstriped color. Having never seen a tasteful luxury automobile with anything but a monochromatic and neutral interior, I've already carpeted and upholstered the Falco in utilitarian gray and black: tough Mercedes-Benz carpeting for the floor, baggage compartment, footwells and forward sidewalls. Half a Connolly hide to leather the glareshield and turtledeck. And some simple tweedy gray for the seats and cockpit sides.

The airframe will be burgundy. Or perhaps a splendidly saturated primrose yellow. Or maybe a rich dark blue. Who knows?

With a kitplane as thoroughly supported as is the Sequoia Falco, the arrival of a new subkit is always an occasion for kitchen-table delights as the box is unpacked. Everything comes in small, carefully marked envelopes, with a laboriously double-checked receipt, and everything is of the highest quality. There are nuts and bolts and washers, but there are also the little treasures. "Oh, my God, look at these cute little brake master cylinders... lookit, lookit, these are the linkages for the gear doors... oooh hey this must be a 90-degree drive for the tach...."

The deliveryman showed up this afternoon with a Sequoia kit called "Fuel System and Engine Hoses." Now these hoses, understand, cost $1,425. Shockingly expensive pipes and tubes, one might say. Except that the large carton contained 159 separate items ranging from rivets to a custom-built aluminum gascolator, a high-quality aircraft fuel-selector valve, quantities of that enormously expensive Aeroquip stainless-steel armored hose and an elegant fiberglass NACA scoop and air-filter mounting that I couldn't have fabricated in 1,425 hours. They were all bagged, labeled, sealed, enumerated, marked, receipted and double-checked.

Sequoia makes a proper profit on every rivet, washer and Aeroquip hose they supply in such a kit and have never said they did anything less. But unless you're an inveterate flea-marketer and full-time catalogue shopper, the cost of the selecting, buying and supplying that Sequoia does for the kit-builder is a substantial part of the value of such subkits.

Anybody who has ever glanced at the range of fittings available for aircraft plumbing has to agree. To make a pipe, hose or tube travel from one part of an airplane to another, there are: branch tees, run tees, street elbows, union elbows, reducers, adapters, sleeves, unions and connectors both male and female. There are: flared fittings, compression fittings, beaded fittings and barbed fittings. There are: hoses described by their inside diameter, hoses described by their outside diameter and hoses described by measurements that don't seem to pertain to either. Some fit into each other, most don't.

If any builder disagrees, Sequoia's Falco plans call out the specification or part number (and, where necessary, the supplier) of every single piece of standard hardware on the airplane. Go get 'em yourself.

This is one of the very few homebuilts to ever have had behind it a full-time company dedicated solely to supplying and helping its customers. In a warehouse in Richmond, Virginia, every day and probably every weekend (I've had my fax messages questioning a minor construction procedure turned around and answered in 20 minutes on a Sunday afternoon), a small but enormously competent Sequoia Aircraft staff is dedicated to this airplane. They're not making some flaky turboprop COIN-fighter prototype or trying to prove that their airplane goes 300 mph or sponsoring race teams, they're simply spending full time supporting a proven, conservative design for a particular breed of builder who wants that and nothing more.

Today I took saw in hand and sliced the Falco in half. It was a wonderful moment, for it meant that for the first time in two years-since I set the finished wing level on jacks and began building the fuselage upon it-there was a major change in the appearance and bulk of the airframe. The barn is now only half full. I no longer have to park the lawnmower under the starboard wing, the snowblower nestled back by the tail, family bicycles filed in odd slots.

If sawing seems an extreme measure to take to change the appearance of an airplane, understand that Frati designed the Falco with this destruction in mind. The ovoid fuselage ring at the rearmost extremity of the wing-root fairing, behind the cockpit canopy, is really two fuselage rings sandwiched together. When the fuselage framework is erected, the two identical frames are bolted together with washers the width of a saw kerf between them. Longerons are laid and glued, the skeleton is sanded and seamlessly skinned, the plywood monocoque is filled and filleted, prepared for paint.

Brook, now 10, holds the last structural piece, similarly autographed by all.

Then you crawl into the tailcone and pull out the bolts, knock out the washers and-assuming you've been smart enough to establish the beginning of a sawcut somewhere before totally veiling the mystery of the kerf-wide gap-cut the tail off your Falco. Just like that.

"I would never cut my airplane in half," said one Falco builder. He was horrified by the insult to the airframe, apparently content to have his entire engine fastened to the fuselage by four bolts yet shocked by the thought of the rest of the machine following it around thanks to the shear strength of 12. Yeah, well if I didn't cut mine in half, I'd have the only Falco Museum in Cornwall, New York. The airplane would never fit out the barn door.

Now I know what it feels like to buy a four-cylinder thumper of an engine that costs more than an entire Japanese car yet looks about as sophisticated as four Beezer Gold Star motorcycles flying in formation. Thirteen thousand and twenty dollars for a Lycoming zero-timed and warranted by one of the finest engine-overhaul shops in the U.S. Everything but the crankcase in my engine is a factory-new part, since the overhauler had no core available. As a favor to a friend who will be sharing the flying of the Falco, he chose to assemble what we needed from his huge parts stockroom.

And that's the brother-in-law wholesale price, since my friend has dealer privileges. The retail figure is-hold still, this won't hurt much-$18,600 for a zero-timed overhaul, $27,415 for a factory-new engine.

There are $6,000 used Lycoming fours on the market. But the thought of sending $6,000 to somebody thousands of miles away for an engine sight-unseen seems horrifying. There's no way to test-drive it, little way to comparison-shop, certainly no resort to honesty in the trade. Why was the engine taken off an airplane if it's in such peachy condition? "Oh, the airplane was wind-damaged while it was parked. Blew over, totaled the main spar but never even nicked the prop," is the usual answer. So usual, in fact, that if you believe that, we live in a nation of constant tornadoes, amid airports littered with Cessnas and Pipers like so many beetles on their backs.

But perhaps I shouldn't be so cynical. One Falco builder set about telephoning airports in South Carolina in the wake of Hurricane Hugo, which only weeks ago caused a calamity in that state. He knows that somewhere down there, the right Lycoming-powered Cessna or Piper is at this moment on its back, a total wreck but for the engine.

The engine option I've chosen is the most powerful one allowed for the Sequoia Falco: a fuel-injected 180-horsepower Lycoming four, exactly twice the horsepower on which the design first flew, in 1955. It's also the rarest. Most builders choose the more widely available IO-320 engine, used in Piper Twin Comanches and a number of other types. Some modify or scratch-build cowlings to accept carbureted 0-320 engines, an even more easily obtainable powerplant, but I want to stick with the sleek Sequoia cowling.

I say "more widely available" and "more easily obtainable" advisedly. In the U.S., the supply of good 320- and 360-cubic-inch Lycoming cores has all but disappeared, for the ones that aren't already bolted to operating production airframes have been sucked up by the booming homebuilt market. There was a day when the engine of choice was a little Continental O-200 or a Lycoming O-235, but today, with Lancairs, Glasairs, Falcos and other high-performance small retractables proliferating, 150 to 200 hp is the most popular power range.

The IO-360-B1E that fits in the Falco powered very few production airplanes-early 180-hp Piper Arrows and Beech Musty-Beer Rs are the only ones I can think of, airplanes quickly superseded by 200-hp versions-so they're almost unobtainable on the used-engines circuit. (The nominally identical 200-hp IO-360 won't fit.)

Certain more common engines can be turned into -B1Es, but with the addition of a manifold here, an injector there, hoses and pipes and elbows and gaskets and all sorts of things that cost the earth. I'm sure one could easily approach the cost of an overhauled engine simply by paying list price for the necessary pieces, so I've taken the coward's way out and gone straight to the zero-timed, dependable, guaranteed block.

There's a disadvantage, though: what one wants to do while flight-testing a newly built airplane is quite the opposite of what is needed to break in a zero-timed engine. On the one hand, for the sake of the airplane you want to make some high-speed taxi tests, a few quick hops, fly around gently with the gear down until everything checks out. On the other, the new engine demands that you spend the briefest necessary warmup time, then get into the air and fly around at continuous high power until the cylinders begin to break in. I don't know how I'll handle that.

I'm secretly amused that friends and acquaintances see the Falco as an example of the great care and dedicated workmanship that I assumedly expend on a project. For that isn't the real me. I've done a lot of half-hearted carpenting-finished most of our house once the frame was erect, built porches and decks and outbuildings, plumbed and wired and poured concrete, worked on cars and motorcycles and even a couple of airplanes. And if there's a thread to be stripped, an irreplaceable part to be lost, a bolt to be dropped into the dark recesses of a timing-chain cover, I'm your man.

I've used screwdrivers as chisels and chisels as screwdrivers. I'm the first to reach for a wrecking bar when a hammer won't do. I've whanged nails into studs at every possible idiotic angle. I'll hacksaw halfway through something and then resort to a mallet. I've rounded more nuts than I care to remember by using a crescent wrench when the proper open-end wasn't convenient.

But building an airplane changes all that, as well it should. Aircraft homebuilding is supposed-by FAA regulations-to be an educational experience, which is why we're supposed to do at least 51 percent of the work on even the most sophisticated kits ourselves. Building the Falco has forced me to use the right tools for the job, to do something over again if it isn't right the first time, to wait until one task is finished before moving on to the next.

There are times when I'll go out to the barn simply to commune with the Falco. Partly because there's nothing much left to do to the airplane-nothing I can work on-and partly because the structure, especially within the confines of the tiny barn, is quite amazing in its size and complexity.

Oddly, I rarely think of flying the airplane and have almost never sat in the cockpit musing about flight, partaking of that classic homebuilder pastime "moving the controls." The airplane has become, to me, a lovely and complicated structure of which I know every cranny and nook.

I'd make an apt vintage-car restorer, had I the talent, for I've always wanted an automobile that I'd "detailed" to perfection-chassis enameled, every suspension piece polished, the fenders as perfectly painted underneath as they are on the outside, every hose and wire shipshape and Bristol-fashion. (I once owned an early DB-4 Aston Martin and was delighted by the fact that the slots in all the screwheads securing the headliner were aligned; I must remember to do that on the canopy frame.)

With the Falco, I can try to do something a little like what I've always wanted to do with an unwieldy car, though I avoid the compulsiveness that drives some homebuilders to finish the insides of wings as lovingly as they do the outsides. But it's infuriating: certain parts need to be painted early, before they're mounted permanently, and the carefully enamel-sprayed control stick is inevitably nicked by the front fuel tank that must go into position and out again numerous times as work progresses. The landing gear, lovingly painted as well, begins to chip and flake a bit where scissors-arms slide against each other and where screwjacks grind the legs up and down. A bit of varnish drips on enameled linkages down under the floorboards, and I must be content that at least nobody will ever see it.

I plan to return to these pages in a year or less to tell you all about the first flight of a Falco. It might not be painted, it might never be "finished," but I really ought to get this creation in the air. My parents are 80, and they want rides.

Still, I remember that too many years ago, when I was an editor at the glorious old Flying magazine, I was the naif who wrote the title "Almost Ready to Fly" for the third installment of Peter Garrison's Roll Your Own, his classic account of building his airplane Melmoth. I'd seen Melmoth, and it certainly looked almost ready to fly... "standin' on the gear, cockpit finished, looked like an airplane." Garrison, who knew better, was shocked. We had to title the next installment, two years later, "Still Almost Ready To Fly."

Am I making the same mistake again?