Moving Day

![]()

Moving Day |

|

Building a kitplane is a one-person job. Getting it to the airport takes a cast of thousands.

by Stephan Wilkinson

Artwork by Richard Thompson

This article appeared in the October/November 1991 issue of Air & Space. |

I suppose there are worse things than watching the airplane you've spent six years and $80,000 to build being moved on a bouncing trailer from a remote upstate New York barn, across a rocky lawn traversed by a brook, down a steep driveway, along a one-lane country road, and then 20 miles down the highway amid Saturday traffic.

The only worse things I can think of, though, are old magazine photos of a country church being hauled down a road on a 64-wheel tractor-trailer while the advance crew dismantles traffic lights. Or of the little guy with a sledgehammer who's about to knock out the last wedge securing a frigate, allowing it to either slide sideways into Mobile Bay or roll over on top of him. Or of the entire Saturn V rocket being trundled to its pad, looking as tippy as a tower-of-champagne-glasses barroom trick.

Many people build airplanes at home. Well, a few do. But more do so every year, as sophisticated kits--giant model airplanes--become available. My Falco was arguably the most sophisticated kitplane on the market. There are others faster, more powerful, and more modern, but believe me, there are none as complicated. My airplane began in the spring of 1985 as a few sticks in the cellar; that summer they grew into a truncated tail section--vertical and horizontal fins, rudder, and elevator, the ghostly lot requiring an active imagination to foresee a Falco.

Going to school on that subassembly, I learned how to bend water-soaked plywood with a steam iron; how to measure in the individual millimeters so crucial to an airframe that would be fitted together as precisely as a pocket-watch; and how to follow the complex choreography of gluing, a dance that moves all too quickly to the finale of sticky fingers and misplaced clamps.

When the main wing spar arrived--a dihedral 26-foot-long splinter of finely wrought spruce, tapering from a center section thick as a railroad tie to hollow, airy tips--it was time to move everything to the barn.

With the airplane safe in the barn, it was a good 200 feet to the house, a distance I had considered an ample buffer for the construction technique known as "shouting it into place." Other crafts people trim, wheedle, cozen, slide, or tap components together. I swear at them, summoning the vilest curses, the most unspeakable, anatomically impossible terms, to humiliate the bafflement into relenting. The barn, unfortunately, turned out to possess the same acoustical magic that domed buildings often have, allowing two people standing far apart to speak at a normal conversational volume and hear each other perfectly. The phenomenon was revealed by my visiting mother-in-law, who sat reading and musing in our living room one afternoon, ceiling fan fluttering overhead, patio doors flung wide to the lawn that lay between the house and the barn.

"It's too bad Stephan hates working on the airplane so much," she said to her daughter.

"Hates it? He loves it," Susan answered.

"Then why is he constantly cursing it, poor thing?"

My father-in-law had even more trouble appreciating the undertaking. He never spoke, never smiled as he poked around the ever-increasing airframe and thought, You brainless dink, all you've built is a pile of firewood trapped forever in an old shed, when my daughter could be driving three Lincolns.

As winter fell heavily upon the Hudson River Valley, I retreated from the numbingly cold barn and began to assemble the airplane's entire electrical system and instrument panel on the kitchen table.

The electrical system kit arrived in a coffin-sized box and included everything from finger-thick battery cables to lightbulbs the size of grains of rice, as well as miles of slick Teflon-insulated wire, cut roughly to length and color-coded. Yellow wire with red, gray and violet striping. Yellow wire with red, blue and violet striping. White wire with brown, blue and violet striping--every combination, it seemed, of nine colors and half a dozen thicknesses. Were I to misread a red stripe for an orange one, keying the microphone might stop the engine. Or perhaps retract the landing gear.

When people saw the airplane a-building, its wings stretching far wider than a door designed to accommodate a hayrick, the first question was invariably "How ya gonna get it out of the barn?" I never had any doubts, for I'd worked the whole thing out on paper, with a little scale outline of the airplane and a floor plan of the barn, its old stalls, and the tree trunk-thick doorposts the wings would have to fit between. But had I measured correctly?

If not, some serious regrouping would be in order, for the airplane was large (26-foot wingspan), heavy (well over half a ton), and at this point, quite unalterable. It was a superb all-wood Italian design of enormous strength and grace. Part of the strength and grace is due to the fact that the wings are permanently affixed to the fuselage in a flowing, sculpted interface. Most airplanes can be dismantled by unbolting their wings from the center section of the spar, but the only thing that comes off the Falco is the tailcone, allowing the airplane to be carried laterally--wings pointing fore and aft--of a flatbed truck.

Years ago Falcos were built in a factory in Milan, then taken to the airport on trucks, trailers, and, at least once, a horse-drawn cart. As moving day approached, I began to worry that my Falco's rollout would prove to be a far less routine journey.

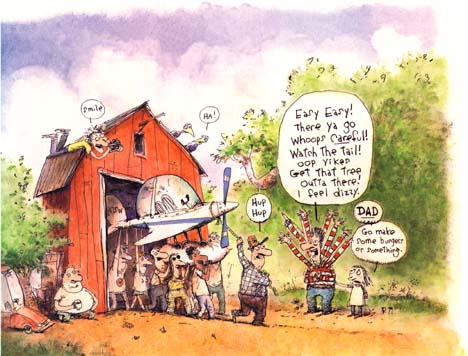

The moving crew began to gather at nine on a Saturday morning--friends, friends of friends, friends' girlfriends, people I'd never even seen before. Among the first to arrive was George, a sinewy, ruddy-faced guy in a Navy cap who quickly took charge. He was a rigger, making his living manipulating huge objects ("George sees steel, his nipples get hard," explained his friend Tony). In minutes George had the Falco out of the barn and onto a borrowed trailer. Hey, this is going to be easy, I thought.

The crowd had grown, now evenly divided between experts and drones. The experts gave orders. The drones drank coffee. But no matter who did what, once loaded with airplane, the trailer wouldn't fit past the tree outside the kitchen windows. "Be my guest," George said with exasperation as Jim, an Adirondacker who handles a chainsaw with aplomb, substantially altered George's plan for chopping the handsomest limb off the tree without letting it crush my Falco.

Six-foot-six Gary, the photographer, did no lifting or toting. "I'm a prince," he said, only partly in jest. "I'm used to working with an assistant, and I'm all alone on this job." Gary dashed hither and yon taking pictures, occasionally backing off a porch, plunging up to his ankle in the brook, or stepping on his camera bag. "Steve! Stand here and talk to Jim. Make believe you're talking abut taking that other tree down."

The Falco's tail was proving to be the most irksome component to move. Though light enough for two people to carry easily--and equally delicate--it was unwieldy, resembling a huge version of a child's jack missing a limb or two. To move it we needed another truck. Tony went to fetch one offered by a landscaper who's also a pilot.

Once the truck arrived, Jim became a flurry of activity, a househusband released for the day from tending his two little boys. "Got any tires? Old tires? How about some more of that foam rubber that's in the barn? Blankets! We need blankets." Four drones trotted past bearing the fragile tail and proceeded to toss it--Oy, I can't bear it--up into the truck, where Jim bedded it down and strapped it in like a gorilla being delivered to Clyde Beatty.

Listen, I'll go rake up grass clippings. I'd rather not watch. Lunch--yeah, I'll make lunch. With my wife away for the week, I'd indulged in all the supermarket excesses she loathes: nine pounds of ground sirloin, six-packs of imported beers I'd never heard of, and boxes of Haagen-Dazs ice cream bars. By the time the hamburgers were on the grill, the crew had everything ready for the tow truck that would haul the trailer. When the Haagen-Dazs bars came out, drones and experts alike were offering to move the barn next weekend if I'd make lunch again.

While we waited for the truck, I recalled the dark thoughts that had occasionally plagued me as the airplane neared completion--images of the first homebuilt Falco to have been completed. First flown several summers ago, it was a stunning, glass-smooth little airplane built by a middle-aged Minnesota insurance executive. Soon thereafter, during a nighttime instrument approach to Gainesville, Florida, the airplane ran out of fuel and went down, killing its builder and a friend. Fast automobiles and high-strung airplanes carry with them a certain cargo of danger. To walk into a showroom and buy such a vehicle can turn out to be a deal with the devil, but to spend years lovingly assembling the instrument of one's demise would be a dreadful indignity.

The tow truck-an enormous van-finally arrived. It would be driven by an acquaintance who owns a company called Musical Waters, a hydraulic extravaganza oddly akin to the butt of David Letterman jokes, Dancing Waters. Bob towed his pumps and hoses, lasers and floodlights to conventions and fairs all over the East, so I figured he ought to be able to tow an airplane.

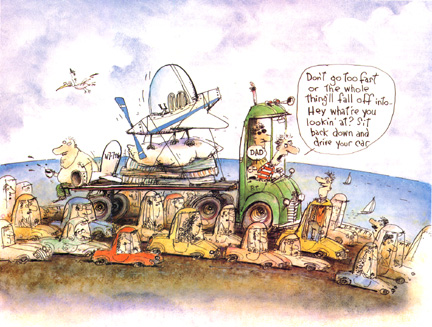

Soon the parade began. The police stopped traffic to allow our caravan-two trucks, a trailer, six cars with flashing lights, and a pickup that appeared out of nowhere-to pull onto Route 9W and head north toward Dutchess County airport, near Poughkeepsie.

But to reach Poughkeepsie we had to cross the Hudson river on an interstate toll bridge, and the Falco was several inches wider than legal. We could hardly hope to slip through unnoticed, but Tony turned out to be a recently retired New York state trooper. "Leave it to me," he said. "They won't bother ya." I had trouble reconciling this pleasant middle-aged model airplane enthusiast with the stock state trooper image: campaign hat creasing a forehead just above mirrored Ray-Bans, frame slowly unfolding from a pursuit Mustang festooned with rotating red lights. But Tony, who led our parade in the truck that was carrying the Falco's tail, negotiated briefly at the toll gate and we instantly became a narrow load.

Drivers in other cars pointed, jabbered , and swiveled their heads as they passed, the Falco's bubble canopy and military-brown primer paint perhaps making it resemble some new, petite stealth fighter. Even more amusing were those who drove by without a glance, as though they saw airplanes being towed along highways every day. Worst of all, however, was the rusty, listing Pontiac that veered into the convoy right behind the trailer, intent on getting a really good look.

My daughter was chattering away in the sing-song Valley Girl voice of 11-year olds everywhere. "I'm reading this really interesting book? By Suzanne Farrell? The ballet dancer?" I paid no attention. "Brook, tell me if you see anything loose on the trailer. Does the Falco's wheel look like it's moving a little? Jeez, is that rope loosening?"

"Dad, how can I distract you if you're going to worry all the way to the airport? Get a life." Like everyone else, she was far more rational about the move than I was. But none of them had built the airplane, had crawled through its innards, had agonized over every curve and conjunction, had sanded and smoothed and perfected for hours. Was it possible to transport such a delicate mass 20 miles without a disaster, without even a ding?

It was, and slowly I realized that the collection of wood and metal I'd sheltered so carefully for six years had better not be all that delicate. For it was not only going to the airport, it was beginning a real life, a life in which it would be rained upon, half-buried in snow, and baked by the harsh summer sun.

It would even fly--there's a thought--while the pounding of its four-cylinder Lycoming engine would rack carefully bonded joints and vibrate compulsively torqued fittings, and the Gs of aerobatics and bad landings would flex and bend an airframe that was not designed to just sit in a barn. Mud would splash its pristine landing gear and oil would streak its smooth belly.

It took 10 minutes to undo what had consumed an entire morning to create. The Falco came off the trailer and rolled into a borrowed hangar like a boxer bounding into the ring. November 747 Sierra Whiskey was finally home.